Story by: Hesham Haj Ali, Paola Floro, Menna Shawky, Xin Chen

Mohammad was 14 when he left Syria. He used to live in the southern city of Daraa with his family, close to the Jordanian border. On March 18, 2011 in the older part of Daraa city, people protested corruption and a recent hike in prices of fuel and food . The government immediately responded with violence. Two people were killed. The situation escalated quickly. More protests erupted and the government’s response was getting more and more violent. The peaceful protests turned to an armed struggle that shaped one of the worst civil wars in history.

In 2012, Mohammad’s family decided that they can no longer live in their little village. The war was less than two years in. He says by that time the government deployed the army to battle the rebels. Land and aerial bombing became a daily routine. “It was simply fear that drove us to leave Syria”, said Mohammad.

He first moved to Egypt and resided with his family in a small town near Al Mansoura city on the Mediterranean. “It was safe to live in Egypt, but it wasn’t comfortable,” he said. It was difficult to make friends, and everything felt different than how it was in Syria. The Egyptians had just elected a president from the Muslim Brotherhood organization, Mohammad Morsi, who voiced support to the Syrian rebels and criticized Assad regime publicly.

After two years in Egypt, Mohammad decided to go to Europe through the Mediterranean with one of his relatives. “I saw University graduates with high qualifications unemployed…I thought then the best thing for my future is to go to Europe.” According to the UN, in 2019, the Syrian refugee crisis entered its ninth year with nearly 5.6 million Syrian refugees registered in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt, and approximately one million newly born in displacement.

67.3 % of Syrian refugees in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon originate from four governorates: Aleppo, Daraa, Homs, and Rural Damascus and 51% of them are children, according to UNHCR.

The Olive Green marks refer to Mohammad’s journey.

Mohammad was only 16 when he decided to go to Europe. His family tried to convince him not to take the dangerous trip, but he had already made up his mind.

On the summer of 2014, Mohammad took a bus to Alexandria in north Egypt on the Mediterranean Sea, there they met the smuggler.

In 2014, more than 200,000 refugees and migrants fled for safety across the Mediterranean Sea. According to a report from UNHCR, the total number of refugees and migrants arriving in Europe through the Mediterranean has been in decline since 2015. Between January and December 2018, 141,500 refugees and migrants crossed the Mediterranean Sea. A report from the International Organization of Migration estimates that approximately 3,270 deaths were recorded in the Mediterranean in 2014. Globally, IOM estimates that over 5,350 migrants died in 2015.

Source: Getty Images

In broad daylight

Mohammad recalls the start of his journey. “They took us on a bus from a public park to a beach in the middle of the city,” he said. The traffickers were not afraid of the authorities and they didn’t try to hide what they were doing. “They did it in broad daylight… we arrived on the beach and later were loaded on small fishing boats, about 4 to 6-meter-long, we were around 15 people on each boat.”

He said after half an hour in the Mediterranean, the small boats stopped next to a larger one and people were transferred to the new boat.

Almost 40 people were transferred to the new boat, but the smugglers had them positioned in different areas of the boat to make it look like they’re part of the crew. The unlucky ones were put in the engine room.

“In the second boat I sat in the engine room, it was small and there was like 15 people inside, it was suffocating…others stood leaning on the boat’s fence and some on the lower level, they did that to deceive the coastguards,” Mohammad explained. They spent almost 12 hours in the new boat.

Later, the boat arrived simultaneously with some other boats and they all stopped near a third larger boat. “The third boat was three stories high, and we were almost 250 people inside… it was comfortable at first.”

After two days at sea, the boat stood still for three days near the Italian territorial waters, it wasn’t clear why to the people onboard. Mohammad saw another boat appear on the horizon. The new boat unloaded more than extra 200 people.

“We had five comfortable days… in the last two days of the trip they got the other 250 people.”

With almost 500 people cramped on the boat now, things became very hard in the last two days. Mohammad says people couldn’t even move to go the bathroom because of how crowded it was. Water started to get into the boat, and it was shaking violently.

“Everyone was fastened in their place, you couldn’t move anywhere, before that we were at least able to go to the bathroom.”

The Italian Navy rescues migrants in the Mediterranean Sea

Italian Coastguard/Massimo Sestini

And finally, we ate

After an entire week in the Mediterranean Sea, an airplane flew over the boat. It disappeared in a matter of seconds. An hour later, a huge Italian warship arrived to rescue them. It sent smaller boats to their boat then transferred the people to the warship.

“If that warship had come anywhere near us, we would have drowned…they sent the small boats for us, and finally we ate,” Mohammad says.

After seven days in the sea Mohammad says they were dehydrated and suffering malnutrition. On the boats the smugglers would give them a piece of bread or a small plate of rice or pasta that would have to last them the entire day. And finally, the men were able to sleep.

“We slept at evening and woke up the next morning on the sound of the warship sailing to rescue another group, we became almost 800 people on the warship.”

Men wearing military uniforms and red cross vests attended to the weary travelers, but only those who could speak English were able to communicate with them. Later they separated the Egyptians from the Syrians and those coming from troubled countries. The Egyptians were sent back to their country, but others like Mohammad were put in camps in south Italy.

“They distributed into camps, they asked for our fingerprints, so we escaped,” says Mohammad. European Union law requires Italy to fingerprint refugees, so that if they apply for asylum in another country they can be sent back to their port of entry. An Associated Press analysis of EU and Italian data suggests that as many as a quarter of the migrants who should have been fingerprinted in the first half of the year were not. While EU law required Italy to share fingerprints for about 56,700 of the migrants, only 43,382 sets were sent.

Mohammad and many others escaped to Milan in the north. The trip took them 11 hours by train. Once there, Mohammad stayed in what he described as an Islamic camp that provided them with some sort of protection from the police.

“We went to an Islamic camp or something like that, in there the police won’t arrest you and force you to give your fingerprint,” Mohammad said.

For two weeks Mohammad and his relative stayed in Milan looking for someone to smuggle them outside of Italy. Finally, a Danish man with a car holding a Danish plate took them to Hamburg in Germany. The 18 hours trip cost Mohammad and the two others who were with him 700 U.S dollars.

From Hamburg, Mohammad was able to take a train and reach his destination country. On August 2014, Mohammad arrived in Gothenburg, Sweden.

According to Statistics Sweden, About 400 000 people immigrated to Sweden between 2016 and 2018. One-fourth of them were born in Syria.

Mohammad lived in Gothenburg for five years, learned Swedish and completed his high school studies. He is now a Swedish citizen and lives in Stockholm where he is studying mechanical engineering.

“The trip was risky; however, it was important for a beautiful future.”

It’s time to leave

“The memory remains filled with a catastrophe, a catastrophe dressed as a revolution.”

Source: AFP

Eman left Syria on November 2016, with her three young kids, Aya 8, Aws 6, and Haidar 4. The journey lead them to travel by plane, train and foot through eight countries before finally reaching their destination, Germany. Leaving Syria was one of the hardest decisions she ever made. “It’s hard to leave your country, to leave behind all that you’ve built… but in the end I decided to leave as I thought there is no hope that the war is ending any time soon, ” said Eman.

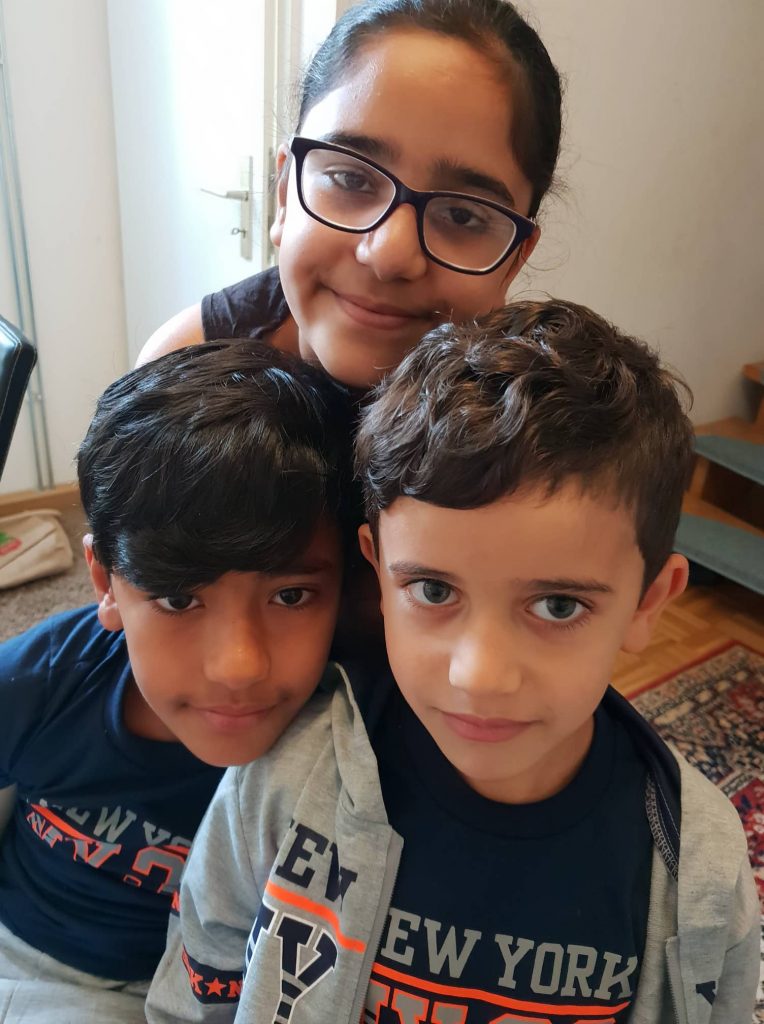

From left to right Eman’s children: Haidar, Aws, Aya

The starting point of the Syrian uprising was in Daraa city. Thousands have been killed since the first protest against the Syrian regime in March 2011. The summer of 2015 was a turning point for most of the city’s residents, including Eman. Rebels in south Syria were planning an offense to take control of Daraa city. On June, 25, 2015 The Southern Front of the rebel’s Free Syrian Army, and the Al-Qaeda-linked (al-Nusra Front) Jaish Al-fatah (the Army of Conquest), both launched operation “Southern Storm”. The results were devastating, thousands of people fled Daraa after the battle. Eman was one of them.

“In this battle the bombing was coming from every direction, most of the bombing targeted civilian areas,” Eman said.

Conditions were miserable. There was no water or electricity while people were fasting for the holy month of Ramadan. “Near the end of the battle a bomb landed near our hose, it shattered the balcony windows and a shrapnel of the bomb was only inches from my daughter’s head.”

Eman saw one of her best friends bleed to death in front of her after being hit by a sniper bullet, her then almost four-year-old son was with her. When the battle ended, Eman made up her mind, it’s time to leave.

She traveled to Damascus and from there took a bus from Al Baramkeh neighborhood to Lebanon.

“When we reached Lebanese borders… women were crying because we knew we’re not coming back. Then I casted the last look at Syria.”

From Lebanon she took a flight from Rafic Hariri International Airport in Beirut to Izmir Adnan Menderes Airport. When she first arrived in Turkey, Eman didn’t know how she would get herself and her family to Europe. Eventually she found a smuggler.

The first time they attempted to flee, the smugglers took the families to a shore, gave each person a life jacket, and told them they were ready to go. Minutes later, whistles were heard in the distance. The smugglers said, “We were compromised. The police are here.” Eman and her children, and other families making the journey were taken to a forest. The smugglers told them to hide in the forest to avoid arrest.

“It was very dark, I was walking in front of my children because it was dark and the trees were huge and I was tripping a lot with their trunks and wanted to warn my children if there is anything ahead.”

After almost a day in the forest she called the smugglers and told them they couldn’t keep hiding. They were taken to a house near the sea. Eman says several families were in the house, around 50 people.

After three days in the house, the smuggler came around 5:30 in the morning and said, “It’s time.”

“When I first saw the sea and the inflatable boats, I thought are we really crossing the sea in this boat? I have heard a lot about people going with those small unsafe boats, but didn’t really think it will look like that.” Eman refused to get into the boat.

Some men were there supervising the situation and making sure everything was going according to the plan. They looked at Eman and said, “You’re going to compromise us.”

Eman insisted she would not get in the boat. “ I didn’t escape death in Syria to get into this boat, it was unsafe.”

The men took her two boys from her and put them on the boat. “I started crying and screaming, then started chasing after the boat with my daughter beside me. They took her too and put her in the boat, then a couple of men held me and helped me get in with my children.”

After almost six hours at sea, they arrived in Greece. Eman explains that during the six-hour journey, she couldn’t raise her head to look around. “I was so scared and so were my children,” she said.

When they arrived in Greece, the red cross was there helping people get off the boat.

“When I looked behind me, I saw the sea. I was stunned, we just crossed the sea. God has helped us survive.”

She says that throughout that day she would go back to the shore and stare at the sea.

“I couldn’t believe we survived.” They were on of the last groups to have migrated to Europe before Turkey closed its borders.

In Greece, it was all very unclear

Eman felt she or her kids could easily get lost in the big crowds. She asked the people around her what to do. They told her to just follow the crowds. They went to Macedonia, Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, and finally Germany. Sometimes by train, sometimes on foot. The hardest part was the walking. “We walked for six hours, it’s even harder with three little kids by your side”. The weather was unpredictable, sometimes it was cold sometimes it was warm. People helped Eman once they realized she was a single mom with her children on this journey. At some point they passed through an area, Eman doesn’t know where it was, where the authorities were beating the men as they passed. She was scared but the authorities didn’t say anything to her. Eman realized it was different for females.

When Eman first arrived in the city of Mannheim, Germany the kids were sick because of their journey. Eman rushed to the hospital. She says she will forever be grateful to the doctor there that took care of her family. After the doctor treated them, she went out and came back with some food for Eman and her children. Eman and her children spent two days in the hospital. When they left the hospital, they moved into a camp. She spent two months at the camp. Eman says, “People in Germany treated us very good.”

The navy blue marks refer to Eman’s journey.

Eman now lives with her kids in a town called Meissen in the suburbs of Dresden city, the capital of Saxony state in eastern Germany. Eman is still learning German. she says the kids, however, are already very fluent and have many friends in their school. Her Daughter Aya is now learning to play guitar and she is one of the top on her class.

Her eldest son, Aws is training with the town’s local soccer team. He says he aspires to play for the country’s most successful soccer club, Bayern Munich.

The youngest one, Haidar is in elementary school. Eman says he learnt German so fast because he wanted to join his siblings in communicating in a language their mother still doesn’t understand completely.

“sometimes they want to hide something, like a story or a detail from me and they will suddenly switch from Arabic to German… I would immediately tell them ‘back to Arabic please’ “. she says the young one sometimes would snitch on his siblings and translate to her what the secret topic was.